In conversation with James Kierstead

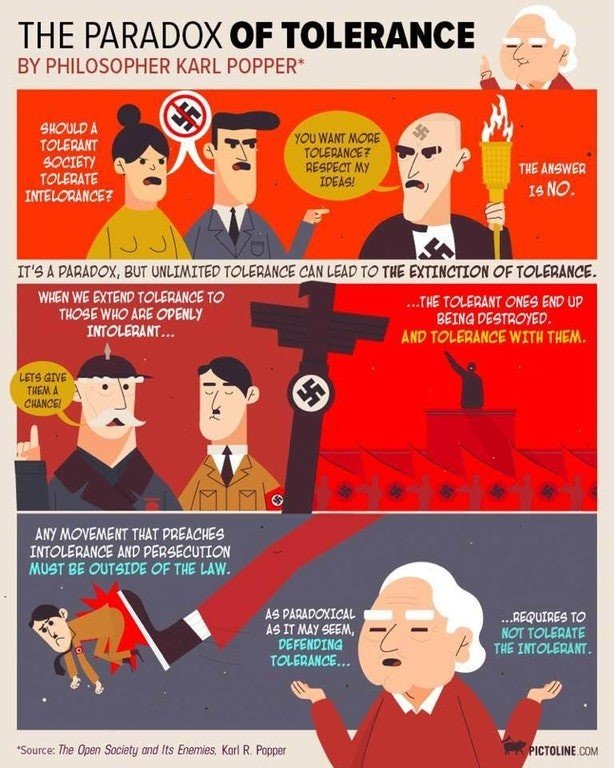

Philosophy has a tragic way of exporting only its worst elements to popular culture. For Popperian philosophy this has been the lengthy endnote to The Open Society and Its Enemies, where Karl Popper digs greedily back into the questions of tolerance and intolerance. The modern references run along similar themes and with similar enemies – Nazis, Islamists, anti-capitalists, communists – substituted into the breach; and because it is popular, catchy, and pseudo-intellectual, most people never actually read the original text, nor do they venture beyond into the wider range of Popper’s work and personal letters.

As endnotes go, even long ones, it is less than “a fully thought-out theory.” But the question itself does matter – it mattered back then, it matters now, and it will continue to matter, as well as continue to challenge the most fundamental notions that we hold about ourselves. Popper may not have dwelt too long – in terms of ink and paper and academic energy – in these waters, but he had been watching them (from near and afar) all his life; struggling with the question: “Where exactly should we set the limits of toleration in speech and action”?

Building-out his arguments for pluralism and accommodation, most of what Popper wrote on tolerance comes to us through the pages of The Open Society. There he uses tolerance as a tool of sorts, a “common denominator” from which we can build a world of extreme difference, and yet have it also remain peaceful and non-coercive. But quoting Voltaire, Popper also saw the harder epistemological edge to it: “What is tolerance? It is a necessary consequence of our humanity. We are all fallible, and prone to error. Let us then pardon each other’s follies’ (Popper’s own translation).

Without tolerance, rationality suffers. We all make mistakes, all of the time; and we only ever see those mistakes – recognising them for what they are, and having the chance to correct them – through criticism… the criticism from other people with whom we also disagree. Sitting in this precarious landscape, the one un-retrievable error that we can make, the one thing that could bring the whole project of enlightenment values and scientific progress and moral improvement down upon itself, is to silence or limit criticism. If you accept that you are fallible, then you must accept tolerance as an “important moral consequence”.

Tolerance must also be an antidote then, a protection against unpleasant worldviews (enemies of The Open Society) that corrupt what we have, and could have. The religious zealots claiming divine sanction, the nationalists claiming ownership over a people's identity, the decoders of historical inevitability claiming to know the future, the tribalists of all stripes and creeds. What they have in common is commitment – commitment to their ideas rather than to truth, and a deep belief that they couldn’t possibly be wrong.

This is where the paradox begins to build. The place where Popper stops his audience and demands something more from them, something more than what his enemies are willing to offer: “We must be tolerant”, Popper wrote in a 1971 letter to Jacques Monod, “even towards what we regard as a basically dangerous lie.” It is an easy thing to dismiss certain ideas as “outdated” or obviously “wrong”, or even to dismiss them for not reciprocating the courtesy that they are given, but we should not forget that the people holding them are largely honest; they believe the things that they say and argue for. They deserve our tolerance.

To not do so, runs its own horrible risks that Popper warned against in a 1973 letter, this time to Paul Kurtz and Edwin H. Wilson: “we must not become dogmatic and churchlike ourselves.” To replace intolerance with a different kind of intolerance, is to not replace much of anything at all. Critical rationalists like himself should be wanting something more, something that breaks with all that prior tradition, rather than continuing with it under different colours.

The trouble hits with a question of functionality and practical decision-making. Imagine that you are the captain of a large ship and you are looking to hire a crew. Just like yourself, they are all fallible and so you don’t expect them all to be particularly good at their jobs. Some are going to be lazy, some will drink too much hard liquor, some might battle with sea sickness, loneliness, or depression. But what you don’t expect is for one of them to not want the ship to float – who, once you are out in the ocean, begins trying to scuttle the hull and drown everyone, along with himself. If you were to know his plan before sailing, what would it say about your captaincy if you allowed him on board anyway? If you discovered his intentions mid-trip but before he could do too much damage, would you have any obligation to keep him on board?

So if we expand this out to a large and functioning democratic society, Popper’s quick reference point is always Germany in the 1930’s (the Weimar Republic) and the rise of Hitler. Popper was of course writing his original passage during the Second World War, and as an exiled Jew he would have been forgiven for thinking about what had happened – and what was happening – in harder, less measured, less philosophical, more emotional tones than that of tolerance and its natural limits.

What matters is always violence. Once you really see it, really feel its coercive shadow, have it change the world around you as well as yourself, it becomes impossible to join in with the apologetics and false analogies:

I shall never forget how often I heard it asserted, especially in 1918 and 1919, that ‘capitalism’ claims more victims of its violence on every single day than the whole social revolution will ever claim. And I shall never forget that I actually believed this myth for a number of weeks before I was 17 years old, and before I had seen some of the victims of the social revolution. This was an experience which made me forever highly critical of all such claims, and of all excuses for using violence, from whatever side. I changed my mind somewhat when Goering, after the Nazis had come to power by a majority vote, declared that he would personally back any stormtrooper who was using violence against anybody even if he made a little mistake and got the wrong person. Then came the famous ‘Night of the Long Knives’ — which is what the Nazis called it in advance. This was the night when they used their long knives and their pistols and their rifles…After these events in Germany, I gave up my absolute commitment to non-violence: I realised that there was a limit to toleration.

All those grand statements about empowerment and human rights and self-determination and everyone expressing themselves and civic responsibility go out the window here for Popper. The reason why democracy is important is simply because it is a means by which we can remove bad leaders and bad policies without having to resort to violence. Neither the intrusive antisemitism he suffered, nor the unpleasant language and speech around him, made the young Popper believe that the line of tolerance had been crossed. The bloodshed and the violence did!

But actual violence seems a high bar, and in later notes Popper begins to flush out the details: “we must not behave aggressively towards views and towards people who have other views than we have” he wrote in his letter to Kurtz and Wilson, “provided that they are not aggressive.” So violence includes the threat of violence – and anything short of that deserves our tolerance, regardless of how nasty, unpleasant, or irrational it appears.

Perhaps all this talk about violence and threats isn’t the most helpful – after all, in often-corrupted modern turns of language, many people will have very different ideas about what those terms mean and what they look like on the ground. A less fashionable, and so more plainly understood term like coercion might be a better fit – something that might still be hard to define when asked, but something that can be easily recognised when felt. Who deserves our tolerance? Anyone who will talk and argue for their theories; anyone who wants to convince you rather than suppress you; and anyone who can be countered by “rational argument” and kept in check by “public opinion”.

The danger now comes from two directions: 1. from the intolerant people and ideas that want to coerce us into supporting them, or into silence, and 2. from ourselves! More than just a core aspect of modern society, tolerance is what makes pluralism and our increasingly peaceful lives possible. And our moral institutions have done a very effective job of building the term into our daily lives and into our identities; to call someone intolerant in this day and age is a burdensome insult that cuts into their very personhood. So we are vulnerable targets of a kind – open to being exploited and shamed into confusion by intolerant invaders, accusing us of hypocrisy for not tolerating them, despite their violence, their aggression, their coercive ideas.

It is not a mistake we should be making. The challenging part of Popper’s brief work on tolerance is its implications which, if you have agreed with him to this point, will appear as unavoidable as they are troubling. The final sentence of Popper’s footnote reads like this: “we should consider incitement to intolerance and persecution as criminal, in the same way as we should consider incitement to murder, or to kidnapping, or to the revival of the slave trade, as criminal.” If you consider intolerance to be as dangerous as Popper does, then this makes clear sense. It should also make you feel deeply uneasy!

In the late 1970’s, Routledge editor Rosalind Hall wrote to Popper. She was seeking his permission to reprint “some” of his footnote on tolerance from The Open Society. Then beginning to see how his words were already being misused and catch-phrased, Popper wrote back saying yes she could, but only if she quoted the entire paragraph, and did not exclude the disclaimer (like so many other people had) that “I want it to be clear that this is proposed by me only incidentally and not as my main statement about tolerance.”

It is never going to be easy, or exact, trying to draw the appropriate limit of tolerance. But reciprocity is as good a starting place as any. It can help to cut through the philosophy and high-mindedness of it all, and instead offer a simple tool for analysing and labelling intolerance in the real world: is the person or the idea across from you playing by the same rules as you? Are they returning the same courtesy that they are being offered? Or are they the dangerous few that Popper had in mind when he spoke about the paradox of tolerance? If tolerance is not a mutual exercise, then one side has an unfair – and unnecessarily generous – advantage.

Later in his life when Popper was visiting the subcontinent, he heard a slightly humorous – and clear – example of his paradox at work. Whether the story was true or just legend, it does something that Popper’s best efforts failed to for so many years – cut through the misunderstanding in a sharp and sudden stroke. It also no doubt helped to endear him to his audience in New Delhi:

“I once read a touching story of a community which lived in the Indian jungle, and which disappeared because of its belief in the holiness of life, including that of tigers. Unfortunately the tigers did not reciprocate.”

*** The Popperian Podcast #21 – James Kierstead – ‘The Paradox of Tolerance’ The Popperian Podcast: The Popperian Podcast #21 – James Kierstead – ‘The Paradox of Tolerance’ (libsyn.com)