It was a new and changing country. The heroes of old novels and propaganda – toiling with brute force against weather, invasion, and internal enemies – wouldn’t work anymore. The gears of revolution were slowly shifting into a new, more subtle age that valued “technology”, “education” and “brainpower”. This was 1988… in Pyongyang!

And what an ominous moment to be alive in that corner of the world. In the right light, at the right angle, and with the wrong eyes, it was still possible to get the sense that the North was winning.

Below the Imjin River, down the banks of the Han, South Korea’s economic miracle was being carved firmly into the landscape. But this was a different age, information travelled a little slower, and geographic borders had a little more resilience to them. Kim Il-sung still had time to turn things around – to bring about the food and the comfort that he had always promised.

Money was borrowed from the Soviet big brother, new chemical fertilizers were handed-out to farmers, terraces were built into the fields, and electric pumps replaced traditional irrigation systems. The once notoriously difficult space of North Korean agriculture was completely transformed, and farmed to impossible new yields.

Everything was looking up, and yet the signs were already there – a famine so agonising and wide-reaching that it earnt its own moniker – the ‘Arduous March’ – was slowly edging its way upon the country.

In a book of the most extraordinary context, it is this look into the near future that is the most difficult to shake when reading Friend. After all, we are dealing with “a state-sanctioned novel, written in Korea for North Koreans, by an author [Paek Nam-nyong] in good standing with the regime”; so much so that our translator, Immanuel Kim, was allowed a private meeting with Paek in Pyongyang.

It starts meek, mild and sad, with a family on the edge of divorce, a husband and wife caught in permanent resentment, and a child lost in the middle. The tenses and time frames bounce back and forth, but it is always Jeong Jin Wu, a provincial court judge that guides the narrative, and balances the emotions.

But ‘moral compass’ is too strong of a term here – the Judge is just as confused and torn as everyone else; he just does a better job with the struggle of it all. Or more accurately, he keeps on struggling where others don’t, his heart still “pained” and his nights still sleepless from a similar family break-up that he adjudicated six years ago.

This time around it’s Sun Hee – a minor celebrity singing at concert halls across the country – and her husband Seok Chun – a lathe operator in a local factory – that have his attention. The couple are both agreed that their marriage should end, their complaints and anger sounding similar from each trench: “…despises me and doesn’t even treat me like a human being.”

The Judge is having none of it! Instead Jeong Jin Wu (his name always written in full, contrasted with the other characters who never get their family names mentioned) promises, with the air of a grizzled homicide detective, that “the court will carefully assess the divorce case”. By this he means, making late night – unannounced – house calls, dropping in casually to interrogate the couple at their work places (along with their bosses), and befriending their young son (Ho Nam) – probing him for information about his parents.

The romance, played back into the history of three different couples, is very 1950s – grand, sudden, and overbearing. After a couple of furtive glances, and disconnected eye-contact, a younger Seok Chun has waited long enough:

“Comrade Sun Hee, do you love me?”

“Huh? Tell me please.”

The intervals between Seok Chun’s breaths became shorter.

“Please don’t do this,” Sun Hee whispered apprehensively.

“You love me, right?” he asked loudly.

“Shh! Someone might hear you!”

“Please, tell me,” begged Seok Chun.

For all that he is to the reader, our Judge was once just as fawning, just as love-struck and pathetic – chasing around his wife to be, forcing himself into her life. The only passion that really steps beyond the North Korean context and resonates to foreign ears is that of “The schoolteacher”. Orphaned by an American bombing raid, she marries an obviously flawed man, tries to change him, squeezes him with guilt, worries herself sick, fails, smiles, laughs and loves him all over again.

Everyone that is designed not to be an obvious villain, is hardworking to a fault. Love always begins by first noticing the passion, the duty, and the effort: “drops of sweat rolling down her forehead, around her lustrous eyes, and down her white cheeks as she arduously worked the press.” From there, it also bleeds into every well placed instinct.

Hoping to reconnect our divorcing husband and wife, the Judge leaves his chambers – and presumably his case load – to dig for sand in a freezing river bed. Dishevelled, he then drags the material back to Seok Chun’s factory, all in the hope that it might help Seok Chun finish his invention sooner, and then have the spare time – once again – for his wife and child. Against this archetype are those “leeches” who “impeded the nation’s progress”: fat, unwrinkled, and “meticulously combed”.

If it all feels a little childish, then that’s the idea! Ever since the Japanese colonial period, Koreans – North and South – have always had an odd image of themselves. Built through layers of propaganda, it was a way to deal with their humiliation and their failure – a coping mechanism for an entire nation. It runs like this:

1. Koreans are a unique and pure race, and morally superior to other races due to this purity.

2. They are all born inherently virtuous, and so their instincts are always correct.

3. But this also makes them vulnerable to foreign invasions: people who take advantage of Korean innocence and good nature.

In a world like this, there is nothing to learn because everything true is already given at birth. People are raised to adulthood always reminded that they should listen to, and embrace, their childish impulses. It is a fairy tale that has lost some of its lungs here in South Korea – in the North however, it is what keeps the regime alive and the people still dreaming of reunification.

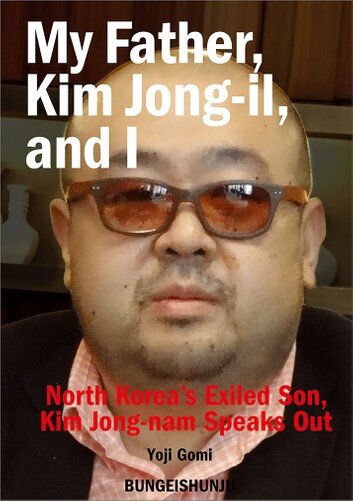

Unlike most dictators, the Kim Trinity are deliberately described in motherly terms, worrying about their people, encouraging them through love and concern, never by example. Already perfect by their Korean blood, North Koreans just need a little nurture and encouragement in their lives.

And here in Friend, the ideological line holds firm: everyone is emotional, passionate to the point of naiveté, and anger always burns righteous, hot and sudden; it’s all very Italian! In a refreshingly subtle and compositionally understated novel, this focus on children breaks the script. Late one evening, Sun Hee returns from her studio to find that the Judge has taken her son to his apartment. Tired, and a little imposed upon, she tries to take Ho Nam back home:

“As soon as Sun Hee grabbed Ho Nam and pulled him into her arms, Judge Jeong Jin Wu reprimanded her in the same way he had at his office.

“Comrade Sun Hee, let the child go. Take him home after he has eaten.”

She realized that the law supported her son’s welfare more than hers, and she cowered before the judge’s sharp words”

The message is clear. There are only mothers here, and so if you ever forget the importance of children, expect others to notice, quickly and without sympathy. But the real error that Sun Hee makes, is trying to direct her son rather than to encourage him to embrace his inner, impetuous, Korean self.

Ho Nam goes with the Judge to his house, and even bathes with him, because on this first meeting the boy “considered Jeong Jin Wu a trustworthy man”. And when one of those “leeches” is trying to convince his mother to finalise her divorce, Ho Nam explodes in adult moral outrage:

“Go home! Take your bread with you,” shouted Ho Nam.

“Have you no respect for family?”

“If you’re family, then why are you telling my mom to leave my dad?”

When the Leech spits back at him, “What an insolent child”, the North Korean audience is supposed to read this as an unknowing compliment.

For all the ideology, there is a lot of the author in this story. Paek’s father was killed during the Korean War, and here the schoolteacher suffers the same fate. He also worked at a steel factory just like our fictional husband, and he was eventually promoted away and into the arts just like our fictional wife. His own wife died young, leaving him to take on the traditionally womanly duties around the house, and Friend is a constant portrayal of the strain and suffering that happens when wives are absent from the household. Paek also came to work at the Jagang Province Writers’ Union, directly above the municipal divorce court, where every day he watched families in the final stages of collapse.

You can hear about the sophistication of the North Korean propaganda machine to nausea, but somehow your expectations still betray you, imagining a crude, blunt force of repetitive prose; every sentence ending with “according to the Great Leader Kim Il-sung”. Not a soft, morally ambiguous narrative, full of parochial dirty laundry.

What runs through it all is change, change, change. Paek was writing at a time when the old literary tradition of Socialist Realism was being swept away – if it ever really existed (See Brian Myers’s Han Sorya and North Korean Literature). Gone were the formulaic and monotonous stories, of “flat” characters and “gung-ho heroes”. In its place an understanding that “proper political indoctrinations cannot make individuals change overnight”.

But this is still North Korea, and writers still work to a script, and a quota. And at times it shows! With Friend the compositional plan breaks down early and fast, with the side-stories around the schoolteacher and her husband –and particularly the old divorce case that the Judge regretfully signed-off on – often undercooked and hollow.

And for all the delicate interplay, there is also a hasty, unpolished element to the prose (to be expected considering that North Korean writers work by assignment), with awkward clichés turning-up and disfiguring the ends of paragraphs:

“The duck would never be the swan’s mate, as their different lives would lead to different destinies.”

“The boy slept, while Sun Hee lay awake in fear that the rain would wash her precious and beautiful childhood memories down the muddied gutters.”

“It was this kind of person who maintained the moral principles of society and washed corrupt individuals out to sea.”

When Immanuel Kim met Paek Nam-nyong in Pyongyang, Friend was already 27 years old – and Paek was “humble, generous, and kind”. Yet it must have felt like something was missing, because in those middle years the world had collapsed, beyond all belief and fear.

First, Kim Il-sung died! Then the Soviet Union collapsed, and without the usual discounts those high-end chemical fertilizers were suddenly too expensive to import. Soon after, an energy crisis put a sudden end to the electric irrigation systems. For the first time in memory, North Korean farmers were abandoned by the state, trying to quickly relearn old techniques for the difficult conditions.

Then the floods came, and with no disaster planning in place, the terraced fields were first submerged, and then swept away entirely. The Arduous March had arrived, with the regime also pushing a new kind of propaganda: “Let’s eat only two meals a day”. Soon it was only one! The whole country was gripped by a biblical famine – even the best attempts of literature to play this down were left referring to it as the “eating problem”.

With shallow graves filling the once-clear hillsides (as a percentage of the population, more Koreans died in the famine than Chinese in the Great Leap Forward), and with stories of Ukrainian-style cannibalism (family members eating young children), a record number of North Koreans risked gunfire to cross the Yalu River into China.

For those who stayed, the starvation ended only when enough people had died – with less mouths to feed there was finally some food to go around. The memory of the famine still lingers in North Korea, it’s not the type of thing that is easily forgotten. And so sentences like this, designed to link motherly concern to the preparation of extravagant meals, would likely make Friend unpublishable today:

“Yeong Il was on the verge of crying and could not control his chopsticks. Next to him was his lunch box, untouched, unopened. His stepmother had packed just rice and boiled spinach. Tears streamed down the schoolteacher’s face.”